Building Real-World Blockchain Technology in Bhutan

A week in one of the world’s most remote landscapes revealed what happens when connectivity disappears, and how new ideas emerge when engineering meets real terrain

By Kostas Chalkias, Chief Cryptographer, Mysten Labs

Most blockchains assume constant internet access.

My recent trip to Bhutan showed how fragile that assumption really is. In a country defined by steep Himalayan terrain, patchy connectivity, and regions served by telecom operators across the border, you quickly see how far theory sits from practice.

Bhutan is also pursuing ambitious digital plans. Its government, investment arm, and technical teams are exploring how modern infrastructure can serve remote communities increasingly connected to global markets. That mix, hard constraints and a willingness to experiment, creates an environment where engineering ideas are tested quickly.

For us, Bhutan offered something rare: a place to see what blockchain looks like when the internet isn’t a given, and where solving problems matters more than abstract claims.

What We Wanted to Explore

At its core, our purpose in Bhutan was to answer a fundamental question: can a blockchain remain useful when the network disappears?

Most systems in this industry assume ideal conditions: stable internet, reliable power, uninterrupted connectivity. But reality rarely matches those assumptions. Mountains block signals. Entire regions operate with intermittent access. If blockchain infrastructure is supposed to serve global populations, it must function in these environments too.

Bhutan gave us the space to explore the problem honestly. Not in simulations or whitepapers, but in a country where the constraints are physical, unavoidable, and indifferent to theory. We wanted to see what survives when you face reality directly.

What We Learned on the Ground

Once we began testing in Bhutan, the environment immediately challenged our assumptions. Local conditions disrupted communication in ways we couldn’t fully anticipate, and methods that seemed reliable on paper broke down.

We had to rethink everything: lighter equipment, shorter messages, new relay paths. Many ideas that made sense in a lab failed in the field. Bhutan forced us to design for the conditions we actually encountered, not the ones systems usually assume.

Exploring Internetless Infrastructure

The work we tested was built around a simple question: How can a remote device participate in blockchain activity when it can’t reach the internet? At a high level, the approach is straightforward. If a device can’t connect directly, it should still be able to:

- Create a secure, tamper-proof message, and

- Have that message carried through the physical world, by whatever means the terrain allows, until it reaches connectivity.

In Bhutan, this meant that a reading from a soil sensor in a remote valley could be picked up by one relay, transported across a ridge, handed off again, and eventually reach a gateway where internet access exists. Once it arrived, the message was verified and published on the Sui blockchain exactly as if it had been sent online.

This turns a remote sensor reading into a verifiable record — the kind of proof commodity and resource markets depend on. The principle is simple: Sign offline → carry physically → verify on-chain.

How the System Worked in Practice

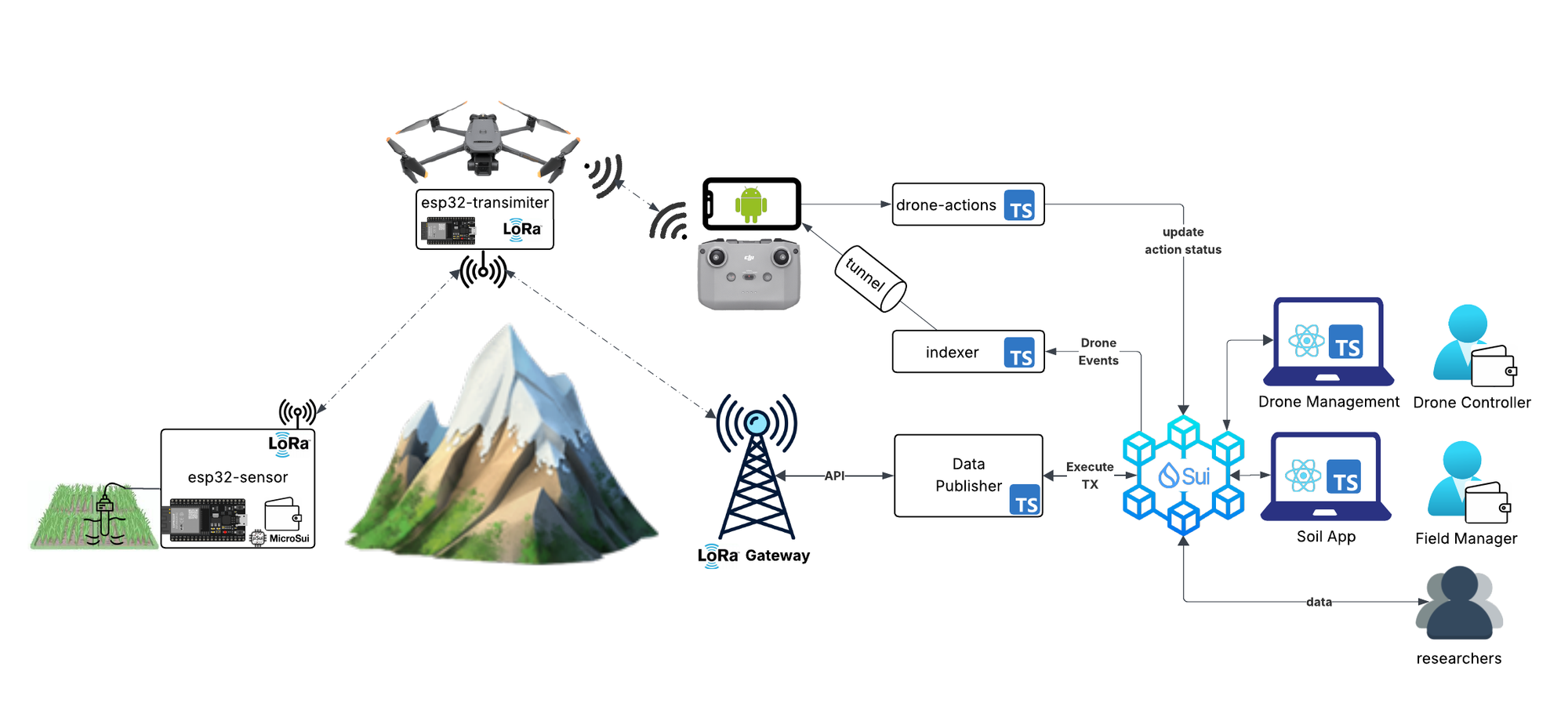

Bhutan’s terrain forced us to combine four engineering approaches:

1. Internetless radio communication. We used long-range, low-cost radio frequencies capable of travelling miles, essential for keeping deployments affordable for rural economies. But steep, rocky hills often blocked those signals completely.

2. Drones as a last-resort “physical crane.” When radio waves failed, drones acted like a physical crane — picking up the signed message on one side of a ridge, carrying it over, and retransmitting it so the next relay could catch it. This could repeat through several hops until a gateway with internet access received the data and forwarded it to Sui validators. In effect, the drone became a mechanical extension of the network.

3. Compressing Sui transactions to their theoretical minimum. Because bandwidth was limited, we had to reduce Sui transactions to the smallest form possible. Instead of sending full transactions, devices sent only the essential, signed intent — just enough for a receiving node to reconstruct the complete transaction and verify the signature.

4. Sensors signing Sui messages directly. Using lightweight microcontroller libraries, sensors could sign Sui transactions on-device, effectively acting as low-power cryptographic wallets. Each message carried its own timestamp and signature, ensuring no impersonation, no tampering, and full data integrity. Because the signature was self-verifying, it didn’t matter how many devices relayed the message along the way.

Why This Matters for Bhutan

Bhutan’s geography makes digital connectivity difficult, but the challenge goes beyond communication. The country is exploring how to bring more of its economy into modern, transparent systems, including agriculture, water resources, and other natural assets that matter for trade and investment.

The problem is simple: if a farm or a forest sits deep in a valley with no signal, how do you prove that the crops or resources actually exist? And how do you build financial products on top of data no one can independently verify?

This is where our work resonated.

We demonstrated that a sensor in a remote field can produce a tamper-proof record, and that this record can still reach the blockchain even when the internet can’t. For Bhutan, that means new ways to establish trust, whether in environmental data, resource management, or the foundations for future services that depend on reliable information.

Why Sui?

What stood out to our partners in Bhutan is the same thing that defines how we work at Sui: we deliver. Many chains talk about what might be possible, but far fewer prove those ideas in difficult environments. That’s why Bhutan looked at who was behind the tech.

Our background mattered. At Meta, I worked on infrastructure that had to operate reliably for billions of people in every connectivity condition imaginable. That experience forces you to prioritise resilience and deliver on what you commit to. It reassured our partners that we could solve problems and meet the reliability expected of critical infrastructure.

Sui also suits this kind of frontier work. Lightweight signatures and fast verification allow tiny, tamper-proof messages to be carried physically and reconstructed once they reach connectivity. That isn’t a bolt-on. It’s how Sui was designed from the start.

For Bhutan, that combination of engineering depth, delivery experience, and hands-on collaboration made Sui the right partner for exploring this infrastructure challenge.

A New Frontier for Applied Innovation

For me, the most important lesson from Bhutan was simple: innovation only matters if you’re willing to test it under real conditions. It’s easy to claim that a blockchain can support offline activity or complex financial systems, but until you stand in a valley with no signal and try to make something work, you don’t really know what your tech can do.

This is the kind of engineering we care about at Sui: applied, not theoretical. We want to build systems that help people who aren’t sitting next to high-bandwidth connections or modern infrastructure. That means designing for failure, for distance, and for environments that don’t behave the way software assumes. Bhutan reminded us that frontier engineering isn’t a slogan. It’s a mindset.

Solve the hard problems first, and let everything else follow.

Final Thoughts: Bhutan as the Beginning

Our time in Bhutan was not a product launch or a commercial announcement. It was an engineering exercise. One that showed us what becomes possible when you stop relying on assumptions and engage directly with real conditions.

The response from our partners there was incredibly positive, and their clarity and enthusiasm pushed us to think even bigger. What we built and tested in Bhutan was only a proof of concept, but it opened a door. The country gave us a place to explore the edge of what blockchain infrastructure can do in the real world.

I’m excited to see where that path leads next.